Published on 10th March, 2021

Professor David Low (1786 – 1888) was a remarkable Scottish academic who managed to persuade the British government of the day to part-fund the setting up of an ‘Agricultural Museum’ at the University of Edinburgh which he would then head. In 1842 he published his groundbreaking ‘Breeds of the Domestic Animals of the British Islands’, the most comprehensive and scientific record of its type for many years and a model for similar publications in several other countries in Europe. In the cattle section are listed and described some 21 British and Irish cattle breeds, together with handsome hand-coloured illustrations by the artist William Shiels who had been sent by Low to tour the British Isles and paint and record examples of the best specimens of the breeds he could find.

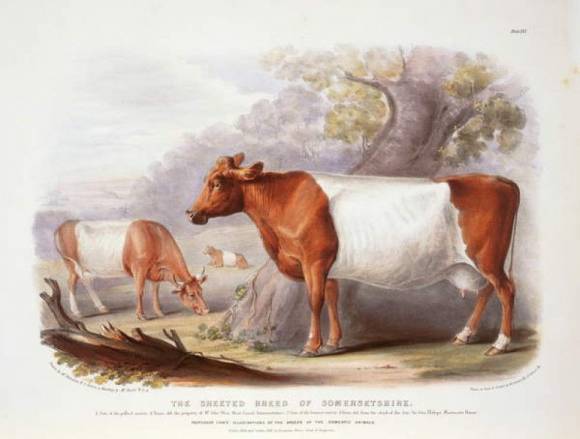

And what did he find in the West Country? The Devon of course, red and horned and still very much with us; but also and arguably the most striking of all the cattle listed, the ‘Sheeted breed of Somersetshire’ which Low described as red with a white marking ‘like a sheet over the body’. Usually polled but sometimes horned, docile and hardy, and both a good dairy cow and a good beef breed. William Shiel’s illustration for the book shows two Somerset Sheeted cows, one polled belonging to John Weir of West Camel, and one horned from the ‘stock of the late Sir John Phelips’ of Montacute House; they are handsome animals and the only sheeted breed listed. Galloways are listed too, but only the black Galloway, although Low does note that Galloways with ‘peculiar markings’ had existed in the past, possibly ‘belties’ or white ridged ‘riggit’ Galloways.

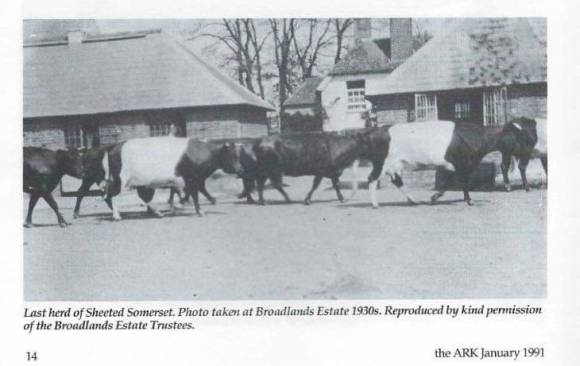

For the Sheeted Somerset to be listed at all suggests it was already a well-established county breed and there are good reasons to believe that it was especially valued as a park or estate breed because of its attractive markings and easy and hardy nature. Indeed Low stated that the breed had existed ‘from time immemorial’ although he went on to note that Sheeted Somersets were already becoming quite rare which he regretted because he considered them much better dairy cows than other breeds which were more popular. Sadly, the breed became much rarer still as the years passed and the last known examples, from the Broadlands Estate near Romsey in Hampshire, were culled in the 1930’s because of TB in the herd. Somerset had lost its only local cattle breed.

Sadder still is that so little is known about the origins of the Sheeted Somerset breed that it cannot be revived, as was done for instance with Belted Galloways and more recently with Riggit Galloways, by selectively breeding from genetic ‘throwbacks’ occurring in the main Black Galloway line. But certain assumptions can reasonably be made; most notably that Sheeted Somersets probably resulted from the deliberate or accidental cross breeding of local West Country red cattle (the forerunners of modern Red Devons) with Dutch Belted (Lakenvelder) cattle which were almost certainly introduced into Somerset in the 18th and early 19th centuries. The Somerset Sheeted was not perhaps a breed originating from ‘time immemorial’ but it was one with a pretty solid past given that few cattle breeds became clearly and scientifically differentiated until the mid-19th century.

The Dutch Belted/Lakenvelder is an interesting beast which exists in both black and red variants and probably originated from the belted version (Gurtenveh) of the Swiss Brown, one of Europe’s oldest cattle breeds. Belted cattle are rare but not unknown in other breeds, notably of course the relatively recent Belted Galloway. But Lakenvelders are special in that until the 17th century their ownership was largely restricted to wealthy and aristocratic Dutch families who carefully bred them as much for their striking looks on their country estates as for their excellent milk – which like water buffalo milk is naturally homogenised.

When ownership became more widespread in the early 17th century, Dutch Lakenvelders became popular house cows, not only in Holland but almost certainly also with the many Dutch and Flemish families who settled in the British Isles in the 18th century and who would have surely taken their most prized possessions, including their prized house cows, with them. And there is good evidence that this happened. John Mortimer, whose seminal Whole Art of Husbandry was first published in 1707, is quoted in the equally groundbreaking Complete Farmer (1st edition 1769) as saying that:

the best (cow) ‘for the pail is the long legged short horned cow of the Dutch breed which is to be found in Lincs and mostly in Kent’. They are ‘tender and require very good keeping’.

Breed names as we know them today did not exist then so one cannot definitively say that Lakenvelders were being referred to but it is highly likely; indeed there is no other credible alternative given how highly valued we know they were for the quality of their milk.

Those Dutch families who settled in eastern Scotland may well have helped introduce the belted gene into the native Galloway cattle; and those who settled in and around the Somerset Levels brought with them not only their formidable skills in draining marshlands for agriculture but almost certainly also their sheeted cattle. It is suggested that Lakenvelders were also imported commercially into the West Country via the ports of the Bristol channel, but although there are records of Dutch cattle being imported for slaughter at Smithfield in London there is no such evidence for such imports to Somerset as far as I know.

The sheeted gene in these early pure bred Lakenvelders was apparently very strong and it is easy to surmise that when crossed with local red cattle, possibly to develop a more hardy cross-breed, it would have consistently produced a striking and attractive white sheet on red beast which would have appealed greatly to local country estate owners who would have been keen to develop them up as a distinct breed; and what else as a name would be better than ‘the Sheeted Breed of Somersetshire’? It is surely no coincidence that both the first and only known painting and the last and only known photograph (to my knowledge) of Sheeted Somersets both feature cattle from well-known estate parks, Montacute in Somerset and Broadlands in Hampshire respectively.

Lakenvelders crossed with local dairy cattle would also been have been popular as docile house cows and were probably equally welcomed by local dairymen and cheese makers because of their superior milk quality. The Complete Farmer of 1769 specifically mentions Chedder as an exceptionally good and expensive Somerset cheese selling at ‘six pence a pound’, and Professor Low’s description of the Sheeted Somersets and their excellence as dairy cattle also references these cheeses ‘made in the area between Chedder and Bridgewater’. This is especially interesting given that several contemporary farmers in broadly the same region have recently introduced Lakenvelders and Lakenvelder genetics into their dairy herds to improve the quality of their milk destined for Chedder cheesemaking.

Sadly, Somerset Sheeted cattle were already in decline before the development in the late 19th century of breed societies, herd books, and systematic and well recorded breeding programmers. As a consequence, we actually know very little about either the early development of the breed or the precise reasons for its subsequent decline; but a series of developments in the early 20th century were to prove terminal. There will probably never be a more attractive park cattle breed than the Sheeted Somerset but the aftermath of WWI saw a massive break-up of large country estates together with their decorative herds; the breed’s role as a house cow would also have disappeared with urbanisation and the development of milk delivery; and there was increasingly fierce competition from newer and more productive dairy breeds.

These and other factors, notably the devastation of WWI and WWII, affected other local European cattle breeds as well; but while some disappeared, others survived long enough to be revived and improved today. Such breeds are valued not only for their cultural and historical value but also for their importance as a source of genetic diversity in a new world of dairy and beef production on an industrial scale that is dangerously dependent on a very restricted cattle gene pool. There are now several well organised groups working to revive Europe’s rare cattle breeds, and it should be no surprise that amongst them is a small farmer-led group in Somerset working to restore the Sheeted Somerset as a recognised cattle breed. The Sheeted Somerset Cattle Society (SSCS) was only formed in 2014 so progress so far has been limited but media interest has been positive and there is real enthusiasm behind the project.

There is significant support in Europe for the preservation and promotion of endangered breeds, and not just from organisations like the Rare Breeds Society in the UK but also from central and regional government in mainland Europe and from projects funded from the EU’s Regional and Rural Development funds. An excellent example of these is the European Regional Cattle Breed (EURECA) project run out of Wageningen University in the Netherlands which looked at a wide sample of ‘at risk’ local cattle breeds across Europe, made strong arguments for conserving and promoting them, and developed strategies and guidelines for achieving these ends. The project predictably identified the key factors that continued to put local breeds at risk, most notably the decline in small farms, the onward march of industrial farming, and the overwhelming dominance of fewer and fewer high input/high output beef and dairy breeds created by modern genetics and spread by AI.

But they also identified a surprisingly strong emotional attachment – including amongst farmers – to old local breeds for cultural, historical and aesthetic reasons. The development of rural tourism and growing popular concern for the environment in general and for threats to food quality in particular can only strengthen this factor. The EURECA study’s guidelines for those preserving, reviving and promoting rare local cattle breeds are no-nonsense advisories which stress the importance of well-disciplined breed societies, and proper registration and performance monitoring. But given the small breed populations involved in rare breed projects there is also a very heavy emphasis on the critical importance of sound breeding plans and of strict measures to maintain genetic diversity.

The practical advice from projects like EURECA will be of value to any small farmer with rare breed livestock, but the Sheeted Somerset Cattle Society (SSCS) and its members face a significant additional challenge in that the effective extinction of the breed in the 1930’s means that few if any of the genetic diversity arguments favouring the preservation of rare local breeds apply to them. There are of course no frozen sperm or embryo samples available, nor are there so far identifiable throwbacks from existing breeds to build on (although Red Devon ranchers in North America have noted white markings that fall well short of a ‘sheet’). Official support from government agencies for their efforts so far have been lukewarm at best; the old Foreign Office advice to its diplomats when faced with difficult requests for help used to be ‘offer them every encouragement short of assistance’, and that comes to mind here. But popular and local media support has been more encouraging and at least two well-known Somerset cheesemakers have also shown clear interest, although they and the general public are probably motivated in large part by the breed’s Somerset association and its visual attractiveness.

If breeding up a pretty red belted cow was all that was required to recreate the Sheeted Somerset then the objectives of the breed society would be fairly simple. Just cross existing sheeted Lakenvelder bulls with appropriate local breeds, preferably Red Devons for historical (or ‘Ruby Red’ for PR) purposes, and on the basis of the old American saying of ‘if it looks like a duck, and quacks like a duck, it’s a duck’, call in Countryfile and Country Living for a televised press conference in front of Montacute House and proceed to name a suitably photogenic and cuddly belted calf ‘ye authentic Sheeted Cattle of Sommersetshire’,

Andrew Tanner and his enthusiastic colleagues in the SSCS have chosen a more serious and difficult path. Many of the historical, cultural, and romantic reasons favouring rare local cattle breeds identified in the EURECA study apply to them also but from the outset they have been clear that:

- the recreation of the breed should follow what little we know about the early development of the breed, notably that it almost certainly evolved from Dutch Belted/Lakenvelders imported by Dutch immigrants to Somerset and subsequently crossed with local cattle. Most breeds of the time, including Devons and Lakenvelders, were dual purpose and this process could have happened in an informal manner way before the highly regularised breeding protocols introduced over a century later. So the initial basis of the SSCS’s Sheeted Somerset Project (SP) has been to use red Lakenvelder bull straws from a major breeder in the Netherlands on a range of British breeds. Some might argue that there are alternative routes to a similar end and outside the SSCS project there are some fine examples of red sheeted cattle in Somerset bred from Belted Galloway bulls, Belties are an attractive breed with a recessive red gene and a strong belted gene so it is not a bad start. And I see some extremely attractive red belted calves every year on the Levels near where I live, progeny of a local Beltie bull put to Herefords.

- A recreated Sheeted Somerset breed can only be viable if it not only displays the visual and other characteristics required of a Sheeted Somerset but is also economically viable for farmers to raise and has a commercially attractive end use. Although the original Sheeted Somerset was very much dairy on the dual-purpose spectrum, the SSCS project has chosen to prioritise the development of a beef variant, in large part because that is where they see the market pointing. This seems realistic as there is a relatively strong market for premium beef and Channel Island breeds already effectively dominate the premium milk market. However, there are two caveats

- Firstly meat consumption appears to be falling as a long term trend and the Red Devon is the choice of already a well-established West Country premium beef brand; also there have been some rather curious choices in which beef breeds to cross with Lakenvelders that make little sense in the context of trying to respect the likely genetic profile of the original Sheeted Somerset.

- Secondly there is already a real interest from several dairy farmers and cheese makers in using Lakenvelder, and perhaps later also Sheeted Somerset genetics to improve the quality of milk for cheese production, this despite some reported problems with milk output from imported in-calf Lakenfelders, and poor teat and udder conformation in early Lakenvelder/Fresian cross cows that will take time to breed out.

It is still early days for the SSCS Sheeted Somerset project which only began in 2014 but there has been some real progress in that sheeted calves with good markings are now regularly being born; DEFRA recognised the breed society in 2018 and it had its first formal Annual Meeting last year; following a meeting with the then Minister of Agriculture George Eustice in 2016 there is now a temporary CTS breed code – LVSP (Lakenvelder Somerset Project) rather than simply LVX; and with some 35 calves registered as such each year there have already been calves sold as Sheeted Somersets in both the Sedgemoor and Frome livestock markets. Had Covid19 not led to the cancellation of the 2020 Bath and West Show it is also highly likely that there would have been some Sheeted Somersets on show for the first time and there is little doubt that they would have been a very popular attraction.

But there have been problems and frustrations too, most notably stemming from the breed society’s poor relations with DEFRA and the BCMS in trying to get a separate and distinct CTS breed code for Sheeted Somersets. Although there are now a small number of Sheeted Somerset breeding bulls, the project so far is still very much based on imported Lakenvelder straws and the BCMS line appears to be that because the project calves are still overwhelmingly Lakenvelder sired LVX or LVSP, there is therefore no basis for calling them anything different. DEFRA have also (as of October 2020) dropped their official recognition of the SSCS as a breed society. The SSCS sees this as deliberately obstructive and unnecessarily bureaucratic but the DEFRA/FAnGR appear equally exasperated, and it must be said that their public documentation on the criteria that must be met to qualify as a native cattle breed clearly set a fairly high bar and this is probably sensible.

There has also been effectively no progress in getting a Sheeted Somerset breeding programme approved by FAnGR despite several submissions. The SSCS, when it was still a recognised breed society, was unique amongst all the recognised cattle breed societies in not having an approved breeding programme. Although I am in no position to comment on where the fundamental problem lay, I suspect there were good reasons for any rare breed society in this position to be very clear and tough in its criteria for approving pedigree status, and very convincing on its proposed measures to both improve the breed and to maintain a healthy level of genetic variation in what will inevitably be a small population. In this specific case I suspect that there may need to be much clearer direction in the choice of appropriate breeds to be put to Lakenvelder and Sheeted Somerset bulls and a far clearer plan on improving the early results to achieve separate breed status. This will almost certainly require a far greater input from partners who can bring the latest molecular genetic techniques to bear, these have revolutionised livestock breeding and are routinely now used to assist in projects to revive historic breeds. The Belgian Rouge Pie de l’Est project is a case in point.

There may also be some useful lessons to be learned from the rather uplifting story of the development of an American Belted beef breed, the BueLingo. Long story short; in the late 1980’s two wise and enthusiastic old American cattle ranchers, working closely with a professor of animal genetics at the local university, decided to breed up a new belted beef animal sired initially by an American Dutch Belted bull; lead rancher Russel Bueling had considered using a Beltie but the breed didn’t cut the mustard. Crossing with Angus heifers helped with getting a line of polled BueLingoes going. Limousin were also tried but were soon dropped as the calves were too nervous and were culled out; and when more dramatic progress was called for, an Italian Chianina bull was brought in. All the while the close association with the university ensured that the breeding programme was seriously designed and monitored, and there was a steady progress from careful pedigree and performance recording, to an official registry and a recognised and strict breed society. All very much in the best gung-ho American style. I have no idea how the breed has fared since, but it does show what clear objectives and very focused decision making can achieve when the right relationship with the quality assurance parties, in this case the university as well as the state authorities, exists.

So where do things currently stand with this ambitious and attractive project to recreate and revive Somerset’s lost cattle breed? To say that I and many others earnestly hope that it will succeed and that we wish the Sheeted Somerset Project every success is of course not enough in itself, but those behind it have been prepared to put real effort and resources into getting things stared and there are already attractive and very visible results to be seen on the ground, and hopefully also soon at the Bath and West and other local agricultural shows. And the breed society’s ambition to create a viable breed with a strong demand for its end product, be it beef or dairy or suckler, makes every sense. But for the project to move forward smoothly will require much better mutual understanding between the SSCS and the Defra bodies whose goodwill is essential to make progress in establishing the Sheeted Somerset as a fully recognised pedigree breed. Some of the language on both sides has been unfortunate but may well point to real issues that can and should be addressed.

But I also believe that there are surprisingly strong societal, emotional and historic reasons that also support recreating the Sheeted Somerset, and they need to feature more prominently in DEFRA’s thinking. Local cattle breeds can never compete in terms of pure efficiency with the modern beef and dairy super breeds that underpin modern industrial livestock farming but as one of the farmers quoted in the EURECA study said, ‘local cattle breeds are an important part of our living inheritance’ in a way that the new super breeds can never be. This is self-evidently true and that makes the recreation of the Sheeted Somerset, Somerset’s only named cattle breed, important for all of those in Somerset who recognise and appreciate our county’s deeply rooted agricultural heritage.

This sentiment is not of course unique to Somerset or this project, there is a much wider issue of why it is so important to protect, revive and perhaps even to sometimes re-create local breeds. Over and above the vital contribution that such measures make to maintaining genetic diversity, the existence of such breeds helps maintain a better and more sane balance between society and agriculture which we like to believe still exists but which in all honesty we know does not for most people, even in a county like ours; cuddly and romantic television programmes on ‘rural life’ are deeply dishonest and do not help . In the modern parlance of agricultural policy makers, I suggest that support to well-argued and well managed programmes in support of local breeds can and should be seen to serve a public good, and that probably requires a change in thinking by ministers and their departments, and perhaps real support and funding too.